Link to this section Overview

Exactly what it says on the tin. It's a Billy Bass fish that's had its electronics replaced and had Motion Sickness loaded on.

For those of you lucky enough to not know what the Billy Bass fish is, let me enlighten you:

And here's the song I loaded on:

Link to this section Motivation

My uncle and aunt asked me to take this one on. The entire project needed to be finished in about a week. I had finals for the first half of the week, and I knew it would take a while to ship to my relatives in California, but I concluded that I could barely make it work if I ordered the parts right away, rebuilt the fish as quickly as possible once they arrived, and shipped the result as soon as possible.

Link to this section Technical Description

Link to this section Hardware and Construction

The chip that controls Billy Bass and plays the default music is covered in epoxy. Much smarter people than me struggle to do this kind of thing. I quickly ruled this option out.

What about using the existing speakers though? Well, at the time, I didn't have a physical Billy Bass handy (remember, shipping...) so I couldn't be sure of the specifications of these speakers.

The easiest solution would be to completely replace the built-in electronics with my own.Knowing that I had only a few days to get this working, and no opportunity to re-order parts if something went wrong, I knew that I needed to get this right.

Normally, I would DIY as much as possible, with hand-soldered perfboards, hectic wiring, and all sorts of bodged-together boards. It became obvious to me that this was the wrong approach here. This was my first lesson: know when too much DIY just won't cut it.

I needed a cohesive ecosystem. Adafruit has been my go-to source for parts over the past couple years, and being based in NYC, I knew shipping wouldn't take too long. But that still left me with plenty of options.

I started by identifying what physical hardware I'd need. Adafruit has a line of boards based off of the VS1053 chip--that takes care of my audio playing. And there are plenty of motor boards available in any form factor I would want. So what do I choose?

Adafruit's board selection generally varies by size and power supply. The VS1053 modules were available in 3 different form factors: a simple breakout board, a FeatherWing board, and an Arduino Shield board.

The breakout board would require wiring it up to a board myself, which eliminated it from the running. Feather boards and Arduino boards are available with any sort of chip, so that's not a concern. What differentiates the boards is physical size and power supply. Feathers are small, and can be powered off of a 5 volt source or a LiPo battery. Arduinos are much larger, but they can take anything from 6 to 20 volts.

Here I faced a dilemma. I wanted the electronics to be small, so that they could fit inside the Billy Bass enclosure without any sort of external box. I also was wary of running the chip and the motors off the same power rail, due to reset issues I'd experienced in the past. The Arduino, with it's built-in power regulator, seemed like functionally the better choice, as it could take a standard barrel plug power supply, run the motors directly off of it, and run the microcontroller chip off a clean, regulated 5V.

However, I wasn't sure if the larger Arduino form factor would fit. I considered rigging something up with a custom perfboard to attach a voltage regulator to the Feather... but I eventually decided against it. I needed to play by the rules of the ecosystem so that I could take advantage of its ease-of-use. I bought the VS1053 and the motor driver for the Arduino.

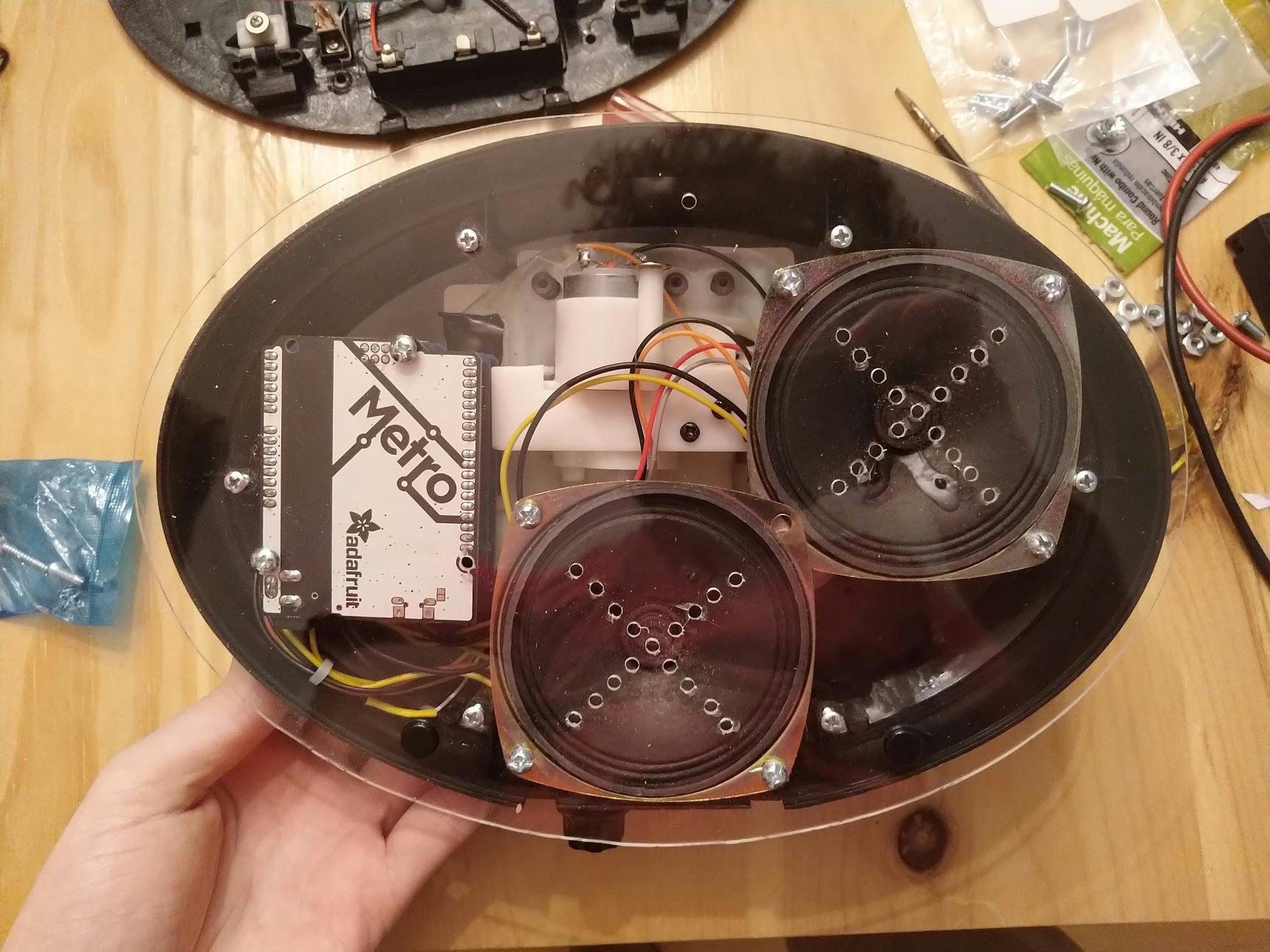

Here's the finished product! You can see the Adafruit Metro (Arduino clone), the speakers, and not much else. Because the VS1053 chip and motor driver were mounted directly on top of the Metro, there was no need for messy mounting solutions or manual wiring.

Link to this section Movement Sync Software

And now, the race was on to get something functional as fast as possible. Getting the song to play over the audio shield and speakers was easy, thanks to the well-documented Adafruit libraries. That left only the fish motion to take care of.

Getting something working this quickly would have been impossible if I had tried to roll my own amplifier circuit, or wire together my own power supply circuit, or do any of that. Here was the ecosystem at work for me, allowing me to go from idea to concept in record time.

The next step was to actually move the fish. I quickly wrote functions to control the fish's head, tail, and mouth, again using the excellent library Adafruit provided for their motor shield. Normally, I would've hacked something together with an L293D in order to save a buck or two. But in this case, the motor shield was worth every penny.

Now, the question is, how do I decide when to activate these movements?

Link to this section Onboard Audio Processing?

The official Amazon Alexa enabled Billy Bass reacts to the audio to decide when to move. This... doesn't exactly work well, as you can see in this Linus Tech Tips review at around the 5:03 mark:

"Okay, so he just kind of spasms then. So basically, you just have like a fish out of water on your wall whenever music is playing."

Yeah... that wasn't gonna cut it.

I decided I needed to manually choreograph the movements to match the music. No reacting-to-audio trickery would save me from this. I did attempt a few basic tests of reacting to audio loudness, but my results were even worse than the fish in that video.

Link to this section Pre-Recording Movements

I realized that I would need to write some custom software if I wanted to precisely record all of these movements in relation to the song. I needed a framework that would let me play audio, handle raw keyboard events, and write in a language I could iterate quickly in. PyGame fit the bill, and I was quickly off to the races.

My script waited for the user to press the space key. It then started playing the music and keeping an internal timer. Then, whenever another key was pressed, it would log the event and the time at which it happened. Finally, it saved it to a JSON file. Pretty basic stuff.

Did I have to decouple the recording from the code generation? Probably not. But I figured it would be best to have a full record of all the movements over the course of the song, so I could try different methods of storing that on the fish if I needed to.

Link to this section Storing the routine

If I had the luxury of time, I might've gone with a packed binary representation like I did for my STMusic project. However, writing the code to generate, store, and load this packed representation would be a lot of work.

I eventually landed on the idea of using a Python script to take the JSON object and generate C code that called each movement function.

import jsonwith open("recorded.json") as file:actions = json.load(file)code = []action_lines = {"head": " fish.head();","tail": " fish.tail();","rest": " fish.rest();","mouthOpen": " fish.setMouth(1);","mouthClosed": " fish.setMouth(0);"}total_ts = 0for timestamp, action in actions.items():total_ts += float(timestamp)millis = int(float(total_ts)*1000)code.append(f" delayUntil({millis});")code.append(action_lines[action])generated = "\n".join(code)with open("routine.ino", "w") as file:file.write("void routine() {\n")file.write(generated)file.write("\n}\n")

Give me a second, I have to wash the blood off my hands after murdering every best practice in the book with this move.

To be clear--this method is ugly. It produces an excessively large binary, it stores data in a file that people expect to be for application logic, it adds an unintuitive step to the build process, it's just generally Not The Way Things Are Supposed To Be Done.

But it worked. It kept the movements synched up to the song. At the end of the day, the future maintainability or extensibility of this program isn't something that mattered that much, and it was a worthwhile tradeoff in order to save some valuable time.

This was the second major lesson. Code quality is good, and good habits exist for a reason, but it's important to decide when things are "good enough" for that specific project.

Link to this section One Last Feature: the volume knob

After putting everything together, I noticed that the fish was perhaps too loud to have in a room. At the last minute, I decided to try adding a volume knob. But how to do it?

The "knob" part was easy enough: I just grabbed some spare parts from my dad's work on repairing guitar amps. On the other hand, the "volume" part presented more of a challenge. Should I go for an analog approach, and try to create a circuit involving the knob that limited the output to the speaker? Or...

I had another idea. What if I used an analog input pin on the Arduino to read the value of the knob, then sent that value to the VS1053 to adjust it's output volume in software? This greatly simplified the wiring, so I went ahead and built it.

Here, I made another tradeoff. I sampled this knob after each movement--not at a regular interval, not at a reasonable sample rate, literally just after each fish movement. And it was good enough! The variable amplitude of the song made the jagged nature of this sampling less obvious.

Link to this section Results

Compromises were definitely made. The lack of built-in batteries made the project significantly more cumbersome, for one. And the motions weren't completely perfect. That said, I'm pretty proud of making what I did in such a limited turnaround time.

This project taught me when good enough was good enough. I sometimes struggle with perfectionism in my projects, where I'll rewrite the same code over and over again in pursuit of a better way of doing things. This forced me to make the tradeoffs I was too scared to make, and to decide what mattered for the final product and what didn't.