Radios are often an afterthought when designing a robotics project. Few robots are self-contained: almost all need to communicate with some external system, be that a basic remote control or a complex offboard system for advanced processing.

Most useful robots also need to operate in an uncontrolled environment. A Roomba needs to connect to a customer's Wi-Fi network, a self-driving car needs to operate reliably regardless of local RF conditions, and a photography drone can't fall out of the sky if an FPV racer sets up shop at the next field over.

My experience with this is primarily in the space of wheeled, "prototype-scale" robots of varying sizes. There is much to consider when scaling up a system beyond one or two prototypes, and the math tends to work out differently for flying 'bots compared to terrestrial ones. (And if what you're building is a boat, good luck -- RF and water do not mix well, and the Fresnel Zone is your enemy.)

Link to this section Hardware

Radio hardware is built for a wide range of applications, meaning it's difficult to even enumerate the options available to you. Especially for a prototype or hobby project, expect to look in interesting places for what you need to make things work.

Link to this section Consumer-Grade Networking

We've gotten quite good at building cheap radios to connect consumer devices over short distances, over Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, or other protocols. While these chips might have been designed for things like smart lightbulbs or wireless headphones, they're often a great choice for short-range networks and can often provide substantial throughput.

Link to this section Your built-in Wi-Fi

Sometimes, the best radio is the one you already have. If your project uses a recent Raspberry Pi model, and your laptop has a Wi-Fi chip, then you're all set for short range communications!

With Wi-Fi, one device must be the access point and the rest are stations (clients). There are a few advantages of making your robot the access point:

- You don't need to configure the robot with the details of your existing Wi-Fi network

- You can operate the robot in areas without an existing network

- You have full control over the channel on which the network operates

- It's easy to connect more devices (e.g., encouraging nontechnical users to connect their phones to try operating your creation!)

This is a great option for running your robot at events where you won't know the setup beforehand, provided you don't expect too many other robots taking up their slice of the 2.4 GHz spectrum.

But it does come with a major limitation: It is generally quite difficult to create a setup in which your robot, as the access point, is able to access the internet via one of its clients. If your laptop is a station on your robot's network, then whoops, it can't be on your home network anymore. Even if you plug your laptop into an Ethernet connection with internet access, good luck getting your laptop to route traffic from your robot to the Internet and back. It can be done, but it takes some complicated network configuration that isn't fun to deal with.

Link to this section Bluetooth

Bluetooth is great as a "it just works" system, requiring just the initial pairing flow before you're off to the races. I used it to send commands to the LED choker that I made. You can get up and running quickly with a microprocessor with Bluetooth support (like the nRF52480) or a drop-in Bluetooth Serial module (like the HC-05 available from tons of sketchy Amazon sellers).

Bluetooth modules are typically much lower power than their Wi-Fi counterparts, don't usually work in a scenario more complex than a point-to-point connection, and have substantially worse throughput. Different Bluetooth profiles support sending different amounts of throughput through, but something like the Serial Port Profile will struggle to transmit images or video.

Bluetooth also doesn't typically use the TCP/IP stack (although it can be done with a specific profile). This is typically fine for microcontroller-based robots, but can make development annoying if your robot runs Linux.

Link to this section External Wi-Fi routers and cards

Still within the consumer realm, some off-the-shelf Wi-Fi routers and cards can be great for getting a bit more performance or range out of a Wi-Fi based system.

Consider a Wi-Fi router on your robot as an extension to the "robot as access point" idea in the prior sections. You get a physical piece of hardware with a sole purpose of providing a Wi-Fi network, along with Ethernet ports to connect any computers onboard your robot. Wi-Fi routers typically use higher power, have better antennas, and can provide more throughput than (ab)using your device's built-in radio.

Alternatively, you can put the router at a base station and connect it (e.g. via Ethernet) to give it Internet access. This gives you the benefits of a wireless network entirely under your control while still giving your robot and ground station Internet access for development.

On the station end, you can still improve compared to whatever built-in adapter you have. Some UAV enthusiasts working on the OpenHD project have identified the Realtek RTL8812AU and friends to be a strong contender, having the maximum allowed 500mW power output, two antennas for diversity and MIMO operation, and support for both the 2.4 GHz and 5.8 GHz bands (which we'll discuss more in the Band Planning section).

Link to this section ESP32 chips

Back in my day, all we had was the ESP8266, a cheap board with no GPIO, bad hardware support, and acceptable 2.4 GHz Wi-Fi in a very cheap package. Nowadays, Espressif Systems has unveiled a line of ESP32 boards with ample GPIO, fast clock speeds, and both Wi-Fi and Bluetooth capabilities.

Choosing an ESP32-based design gives you lots of options for small robots, either as the robot's primary microcontroller or as a peripheral. For instance, you can use Bluetooth to set up the initial connection, then let the user input their Wi-Fi details and switch to that connection. Or, you can use Bluetooth for telemetry and controls, while keeping a Wi-Fi link during development for stronger visibility.

Of course, this series of chips is in the microcontroller realm, so they won't be able to push through as much throughput as a dedicated Wi-Fi router or card. for small and short-range projects, however, they can be a strong contender.

Link to this section Drones

The world of UAVs has brought forth many unique solutions for radio communication. Unlike wheeled robots, you can typically assume that a drone will maintain line-of-sight with the control station at all times, giving signal penetration a lower priority. Drones also are extremely sensitive to weight, so solutions tend to be compact and simple.

One quirk of drone communications is that drones typically use two frequencies: one for control and basic telemetry, and another for FPV/video streaming, leading to two very different sets of solutions.

For controls, the RFD900 is by far the most well-known choice. It provides a basic serial connection which typically facilitates the transfer of Mavlink messages. Unlike any of the other solutions we've looked at thus far, the RFD900 works on the 900 MHz band.

The RFD900 uses frequency-hopping spread spectrum: the specific frequency used will jump around in the 900 MHz band to avoid interference. This is great in a scenario with other RFD900s (like an FPV drone racing event) since they'll generally stay out of each other's way.

FPV drones also typically use analog video systems. There are a few reasons why these have stuck around, even though they use spectrum far less efficiently than digital systems:

- Since digital systems need to perform video encoding, analog video requires much less hardware, saving weight

- Analog video tends to degrade gracefully under interference or poor signal conditions

- Since drones typically operate under line-of-sight conditions, they can use higher bands (most commonly, 5.8 GHz) which allow for wider channels

Because of this, analog video gear is generally commonly available. If you're working with a small robot with only a single camera over a relatively short distance, this can be a good solution. However, note that you can't perform any onboard processing with such a camera.

Link to this section WISP Gear

Wireless Internet Service Providers, or WISPs, are companies that provide Internet access to customers using wireless links as opposed to wired (fiber or copper) connections. Equipment made for WISPs is built to be reliable, designed for long-term operation, highly configurable, and to operate right up to the power limits allowed by law.

Ubquiti products are cheap and work well, including the Rocket and Bullet series of radios. Each line comes in 2 GHz and 5 GHz variants, with 900 MHz variants discontinued but often found on eBay.

For stronger 900 MHz capabilities, consider the Cambium PTP 450 900. Note that these use a proprietary protocol. While Cambium makes some other variants, they're either difficult to get licenses for (like the PTP 450 on 3.65 GHz) or prohibitively expensive for most use cases (like the PMP line, which supports point-to-multipoint scenarios across many band types).

These radios provide an Ethernet port and can effectively make your network look like a flat Ethernet subnet, greatly simplifying your configuration. Alternatively, many Ubiquiti radios can be configured to operate as a standards-compliant Wi-Fi hotspot instead of in point-to-point mode, allowing you to combine a high-powered WISP radio with inexpensive consumer Wi-Fi gear.

Link to this section Packet Radio

A promising method I've been looking for an excuse to use is low-cost packet radio modules. These implement a barebones protocol without any sort of pairing, connection, or scanning logic. They typically support relatively slow data rates, but can cover a relatively large area.

These radios tend to transmit in one of two bands:

- 433 MHz: Generally unlicensed in Europe, licensed in the Americas (although usable with an Amateur Radio license).

- 900 MHz: Unlicensed in both Europe and the Americas (albeit slightly different bands, 868 vs 915 depending on region). This can be a blessing (it's easier to get started with) or a curse (in the US/Canada, there are many more devices in this band than in 433).

An iteration of these uses LoRa, a modulation technique that enables much farther communication (although this increases cost).

Link to this section Amateur Hardware

Another source of radios is hardware designed for amateur radio use. These operate on a huge range of bands, but typically focus on voice transmissions. The digital modes that do exist are intended for short, infrequent messages. This is typically not a good fit for a robotics scenario, but it could be useful.

On the absolute low end, you can always use a cheap Baofeng radio (usually ~$20 USD on Amazon) with your computer's sound card and some software for a basic digital mode.

Of course, amateur hardware also has restrictions (e.g., no commercial use) which we'll talk about more when we discuss amateur licensing.

Link to this section Band Planning

When picking a radio, you'll often want to consider the frequency band it transmits on. Specific bands have certain innate characteristics which make them more or less suited to a given application. You'll also need to consider other radio systems within your robot and ensure you do not cause interference.

Different bands have different strengths and weaknesses. Generally, lower frequency bands will provide better signal penetration and non-line-of-sight operation (e.g., operating your robot from the other side of a wall), while higher frequencies are better suited to line-of-sight or short-range uses.

An advantage of higher-frequency bands is that they generally can provide much higher bandwidth, both via higher signal rates and wider channels. If your system involves streaming lots of high-resolution video, point clouds, etc., you will probably struggle on a lower-frequency setup.

If your robot has multiple communication systems, you'll need to make sure you aren't causing interference to yourself. This could take the form of multiple links to your base station (such as separate links for telemetry and video), or it could arise in a system with multiple interacting robots.

Generally, for multiple radio links to your base station, you will want to put each link on a separate band to minimize interference. For instance, many drone pilots use 900 MHz or 2.4 GHz for teleoperation and 5.8 GHz for video streaming.

Interference can also be tricky to identify the source of. On the Rover team, we noticed an issue with our 900 MHz radio gear interfering with our high-precision GPS receivers, preventing us from attaining a precise fix.

Your robot might also need to operate in an area with lots of interference, such as a Maker Faire, in which the sheer number of users on the 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz bands can make protocols like Wi-Fi almost unusable. While frequency-hopping protocols can work more reliably, they still have their limitations.

Link to this section Amateur Licensing

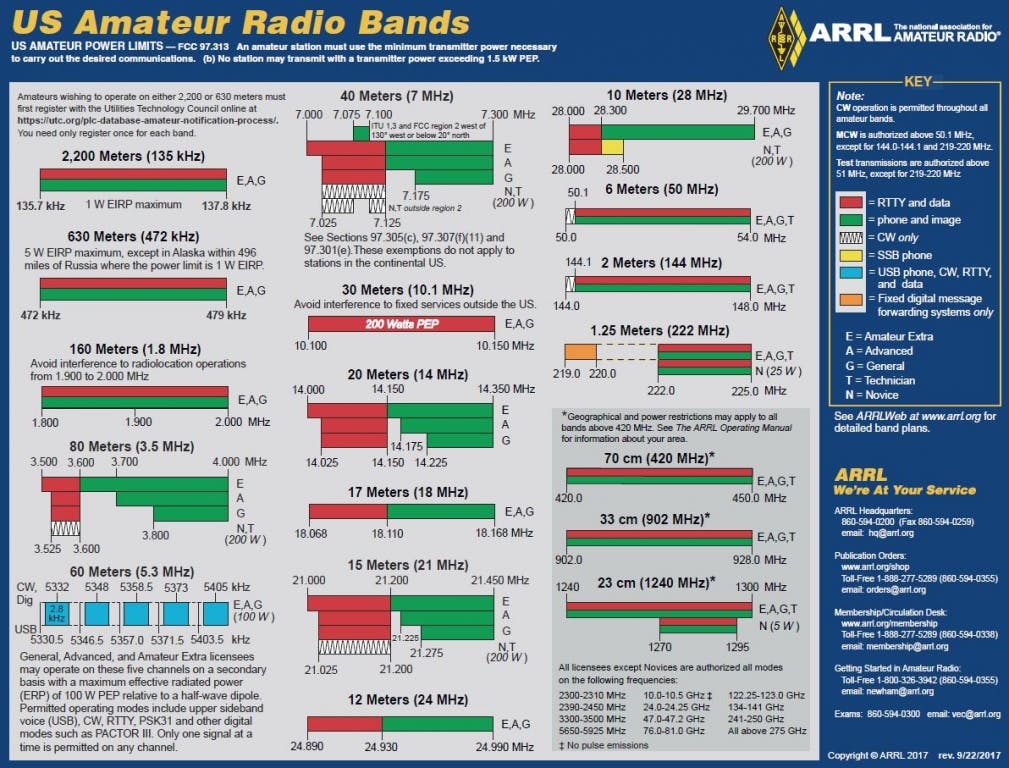

If you're a hobbyist, you aren't just limited to the ISM or unlicensed bands: the Amateur Radio Service is there for you! Getting an amateur license gives you access to a much larger array of bands across a wide range of radio spectrum. While this varies by country, most countries do something similar to the U.S.:

The most important restrictions to keep in mind are:

- Your use-case must be for a non-commercial purpose.

- You generally cannot use encryption (although there's some debate on this). You definitely can't use encryption to hide the content of your messages.

- Any data protocol you use must be publicly documented.

- You need to obtain an amateur license, and you must identify with your callsign once every 10 minutes during transmission.

Getting licensed is generally straightforward (Becky Stern's article gives a good overview of the process). A few tips from my own journey:

- If all you care about is passing the test, just go on hamstudy.org and memorize the questions for a few hours. There are resources that you can pay for to learn the concepts in more detail, but it's not necessary.

- You'll initially be assigned a random callsign, but you can apply for a vanity call immediately afterwards for a small fee.

- If you're a college student, see if there's a club on campus that runs exams!

In the U.S., there are a few classes of license, and most countries follow a similar structure. At time of writing, I hold a technician class license, and it gives me almost all of the same privileges as the higher classes on the shorter bands (433 MHz and up).

Some amateur bands overlap with unlicensed/ISM bands: the 33 centimeter amateur band takes the same space as the 915 MHz ISM band, the 2.4 GHz amateur band partially overlaps the ISM one, and the 5.8 GHz amateur band is a subset of the spectrum set aside for Wi-Fi. In these bands, you can often use commercial grade hardware at higher power limits or with larger antennas -- for instance, running a Ubiquiti access point on 2412 MHz at maximum power with a high-gain antenna. This gear generally isn't designed for use above the unlicensed limits, so you won't always gain a significant boost, but it can still give you a bit more range.

Other bands are generally pretty quiet except for amateur users:

- The 2 meter and 70 centimeter bands are predominantly used for analog FM voice, although the 70 cm band overlaps with the unlicensed 433 MHz band in Europe (meaning you can find consumer hardware which operates on it)

- The 23 centimeter (1240 MHz) band is generally pretty empty, although it is right next to the frequencies used by GNSS (e.g., GPS) receivers which can cause problems, and it's tough to find hardware for

Link to this section Conclusion

Based on my experience so far, I've developed a few rules for selecting which system to use:

- Start with Wi-Fi. It covers a surprising number of use cases regarding range and data throughput, and hardware is common, cheap, and lightweight.

- Punch through obstacles using either higher power or larger wavelength. If you're going a significant distance through a forest, for instance, you'll probably struggle with consumer Wi-Fi modules. You could switch to a larger wavelength like 900 MHz, which can better penetrate obstacles, or you can stay on 2.4 GHz but switch to following amateur regulations and using WISP gear and high-gain antennas.

- Consider more specialized systems if needed. You might struggle to find components to run on other bands or using different protocols, but it's sometimes the only way to satisfy an unusual use case.