This blog post follows my journey to learn about reverse-engineering on Android over a few months. Unlike a traditional project writeup, the structure of this piece matches the process of discovery I took. Dead-ends, useless tangents, and inefficient solutions have been intentionally left in.

Link to this section The Idea

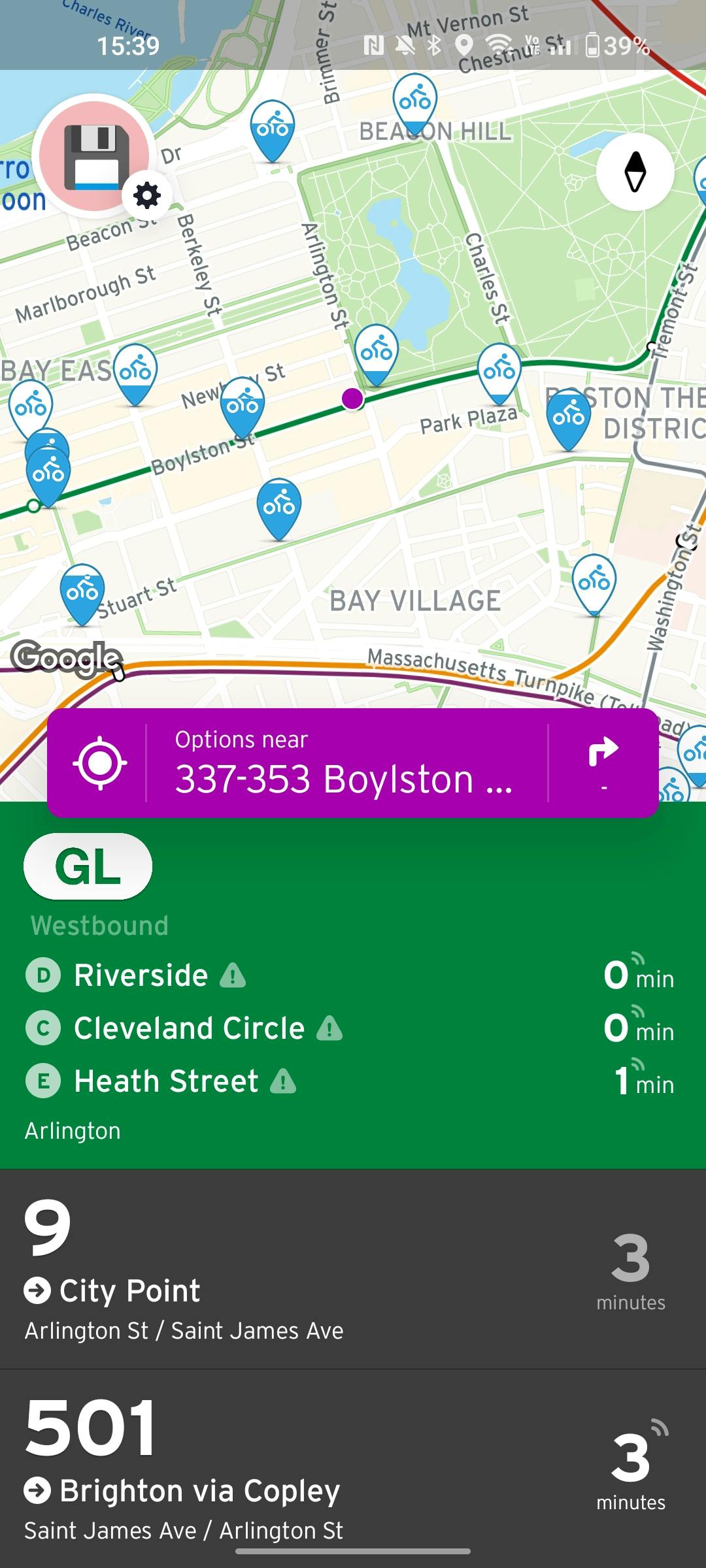

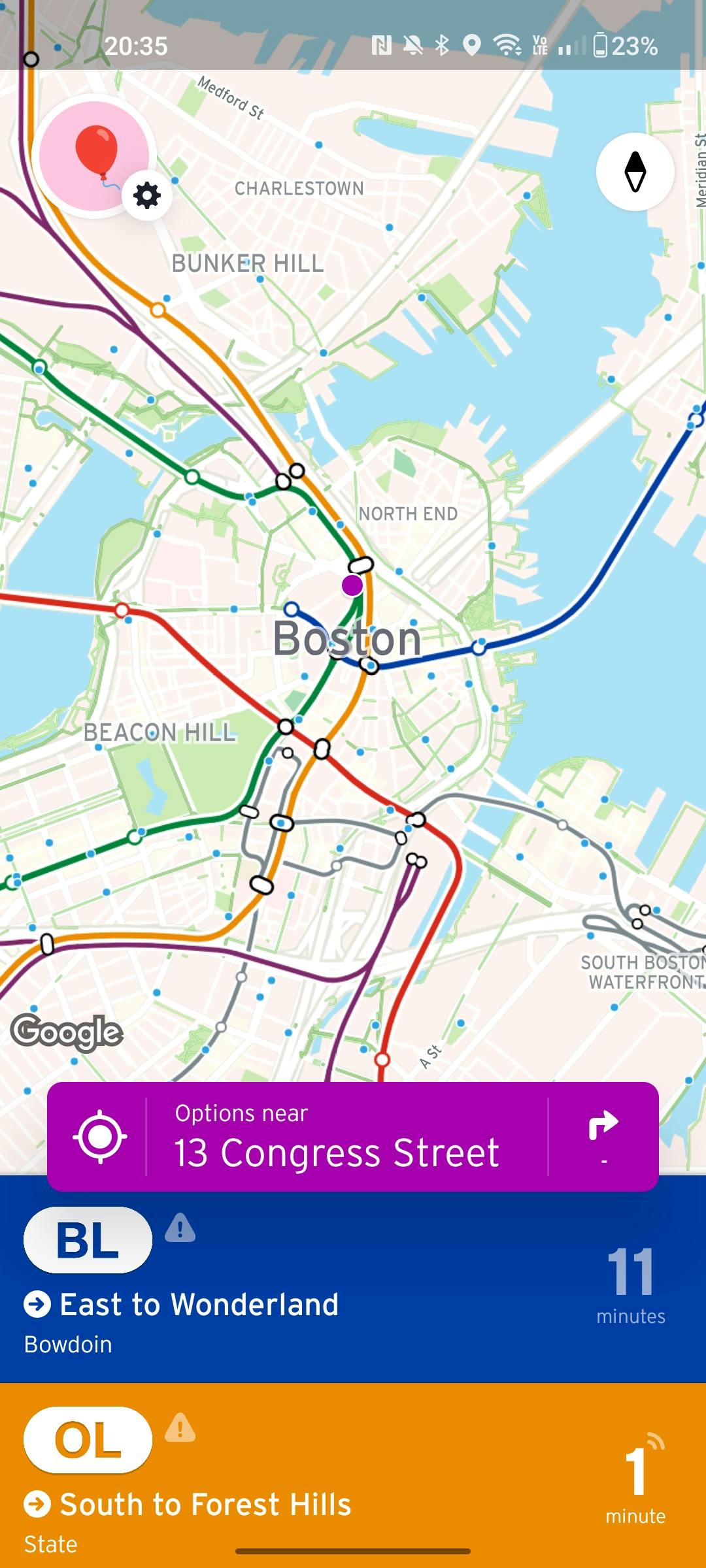

I live in Boston currently, which has a wonderfully extensive transit network. To navigate between unfamiliar areas, I use an app called Transit. Transit (or TransitApp, as I tend to call it) tracks bus, train, and subway departures in realtime to provide directions and time predictions.

TransitApp also has a "gamification" system, in which you can set an avatar, report the location of trains from your phone, and show up on leaderboards.

Instead of public-facing usernames or profile pictures, TransitApp's social features work off of random emoji and generated names. You are given the option to generate a new emoji/name combination.

For reasons I won't get into, I really wanted the 🎈 emoji as my profile. It's not on the list of emoji that the shuffling goes through (I shuffled for quite a while to confirm). If you pay for "Transit Royale" (the paid tier), you can choose your emoji yourself. However, I was bored, so I decided to see if I could find a more fun way to get it.

My hypothesis was that the app is doing this "shuffling" logic on the client side, then sending a POST request to the server with the emoji to be chosen. If true, this would mean that I could replay that request, but with an emoji of my choosing.

Link to this section Methods

Link to this section Android Emulator

Because messing with a physical Android device seemed tricky, I decided to try using the Android emulator built into Android Studio. (No need to create a project: just click the three dots in the upper right and choose "Virtual Device Manager.") After picking a configuration that supported the Google Play Store (I chose the Pixel 4), I installed TransitApp and logged in without issue.

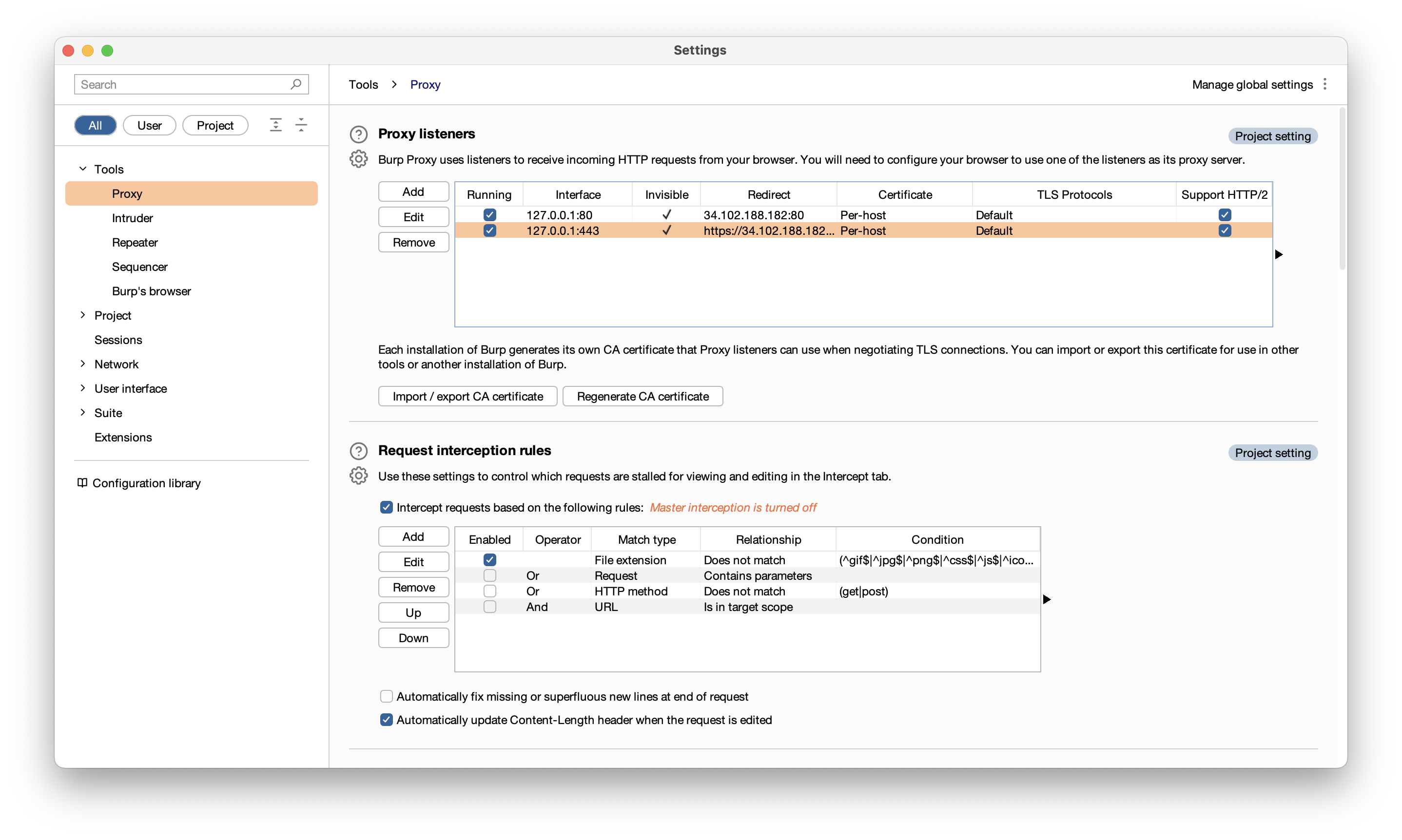

Link to this section Burp Suite

Burp Suite is the standard tool for inspecting and replaying HTTP network traffic. Burp Suite creates an HTTP proxy, and is able to inspect traffic via this proxy.

I began by setting Burp to bind on all interfaces, then set the proxy in the emulated phone's settings to point at my computer's IP address and proxy port.

Burp Suite's analysis tools effectively break HTTPS, since it's the literal definition of a man-in-the-middle attack. In other words, TLS protects the connection from my phone to any cloud services, and for Burp to mess with that, it needs a way to circumvent TLS. One approach is to install Burp's certificates as a "trusted" certificate, effectively making Burp Suite able to impersonate any website it wants.

Most guides for manually installing CA certificates on Android require a rooted operating system, but with a reasonably recent OS, it's possible to install them in the phone's settings, by going to: Settings -> Security & privacy -> More settings -> Encryption & credentials -> Install a certificate -> CA certificate. This adds a "Network may be monitored" warning to the phone's Quick Settings page.

This works perfectly! Now let's just fire up TransitApp, and... nothing. It looks like TransitApp doesn't respect the user's proxy settings.

A few apps claim to be able to use a VPN profile to force all traffic over a proxy, but this seems to not work properly for any I tested.

Link to this section Wireshark

Wireshark is a much more general-purpose network traffic capture tool. It supports capturing network traffic and filtering, making it relatively easy to inspect traffic.

However, Wireshark cannot circumvent TLS. As a result, even though the presence of traffic is visible, it cannot be actually inspected. When filtering for DNS traffic, though, we do get something helpful: the domain names that TransitApp uses. We see a few:

api-cdn.transitapp.comstats.transitapp.comservice-alerts.transitapp.comapi.revenuecat.combgtfs.transitapp.comapi.transitapp.com

With the exception of RevenueCat, which seems to manage in-app subscriptions, all domains are *.transitapp.com.

Link to this section Burp Suite Invisible Mode

Burp Suite's Invisible Mode allows the proxy to work for devices that aren't aware of its existence, by relying on the host OS to override DNS queries for the relevant domain names and send them to the proxy instead. To get this to work, we can run the Burp .jar with sudo, then set up two proxies: one on port 80 for HTTP and one on port 443 for HTTPS. Make sure to enable "invisible proxying" for both.

Since we're using invisible proxying, we'll need to explicitly tell Burp where to forward the traffic -- the HTTP(S) requests themselves won't have enough information for Burp to route them onwards. We can make a DNS request to find the IP address of the serer hosting api.transitapp.com:

$ dig @1.1.1.1 api.transitapp.com; <<>> DiG 9.10.6 <<>> @1.1.1.1 api.transitapp.com; (1 server found);; global options: +cmd;; Got answer:;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 38753;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 1, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION:; EDNS: version: 0, flags:; udp: 1232;; QUESTION SECTION:;api.transitapp.com. IN A;; ANSWER SECTION:api.transitapp.com. 248 IN A 34.102.188.182;; Query time: 55 msec;; SERVER: 1.1.1.1#53(1.1.1.1);; WHEN: Fri Jun 16 18:27:14 EDT 2023;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 63

Configure both proxies to route traffic to that IP address, keeping the ports the same.

If you've played with networking before, your first instinct will probably be to mess with the /etc/hosts file to override DNS for the domains you want to intercept. This is a pretty common technique for web-based attacks, so let's give it a try. One hiccup: we can't put wildcards directly in /etc/hosts, so we'll have to list each one individually. Worse, we'll actually have to only do one at a time, since Burp Suite can only forward traffic to one IP at a time. Start with api.transitapp.com.

Aaaand... it still doesn't work. Android is using something called Private DNS to automatically route traffic over HTTPS, meaning it can't be tampered with as easily as traditional DNS. But even if you turn that off in the emulated phone's network settings, it still doesn't work, because the emulator doesn't respect the /etc/hosts file. You'll need to run a DNS server.

First, find the IP address of the emulated phone and your computer. In the phone, go to the network settings page, then look for "IP Address" and "Gateway": those are the IPs of the phone and your computer, respectively.

Install dnsmasq on your host computer and run it (here's a nice guide for macOS). Set the Android DNS settings to point to your computer's IP. And then update your /etc/hosts entry to point to the IP address of your computer on the network instead of 127.0.0.1, since otherwise the emulated phone would attempt to connect to itself.

Even still, this doesn't work. If you try to inspect traffic, relevant features of the app will simply stop working and you will not see any connection trying to be made.

Link to this section Static Analysis

Maybe some static analysis could help? We can download an APK from a definitely legitimate source, then unzip it (.apk files are just .zip files).

The first thing we can do is to start looking for URLs. We already know that some URLs start with api.transitapp.com, so let's try looking for that:

$ rg "api.transitapp.com"

No results. What about just "transitapp.com"? Still nothing.

It could be substituted in somewhere. Maybe we could look for the beginning "http" or "https" part of a URL?

$ rg httpassets/cacert.pem9:## https://hg.mozilla.org/releases/mozilla-release/raw-file/default/security/nss/lib/ckfw/builtins/certdata.txtokhttp3/internal/publicsuffix/NOTICE2:https://publicsuffix.org/list/public_suffix_list.dat5:https://mozilla.org/MPL/2.0/META-INF/services/io.grpc.ManagedChannelProvider1:io.grpc.okhttp.dgoogle/protobuf/source_context.proto3:// https://developers.google.com/protocol-buffers/google/protobuf/empty.proto[many similar protobuf results omitted]META-INF/MANIFEST.MF494:Name: okhttp3/internal/publicsuffix/NOTICE497:Name: okhttp3/internal/publicsuffix/publicsuffixes.gzMETA-INF/CERT.SF495:Name: okhttp3/internal/publicsuffix/NOTICE498:Name: okhttp3/internal/publicsuffix/publicsuffixes.gzres/56.xml2:<resources xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools"res/sd.xml6:<resources xmlns:tools="http://schemas.android.com/tools"

Okay, that's interesting. "okhttp3"? This seems like it could be related to how the application makes HTTP requests to the API. But this still leaves us with a few questions:

-

Why weren't we able to find the URLs? From a bit of research, it looks like Android apps store Java code in

.dexfiles: the Dalvik Executable Format. (Dalvik is the name of the virtual machine used to run Android apps.) It is possible that this format uses compression or other techniques which would prevent a literal string from appearing. Runningrgwith the-aparameter does show some matches in a binary file, but they seem to be in a section of the file which just stores string literals, and based on the limited number of matches, it is likely that URLs are assembled at runtime (meaning we won't find a fully-formed URL in the source). -

Why did the app refuse to connect via our monitoring setup? Here's where we need to dig in to how OkHttp works a bit more.

Link to this section Certificate Pinning

OkHttp is a library made by Square for making HTTP requests on Android (or other Java platforms). The fact that it was developed by Square, a payment processing company, is a clue that they might be taking steps to secure the connection that most apps wouldn't.

Here's a snippet from the front page of the OkHttp documentation, emphasis mine:

OkHttp perseveres when the network is troublesome: it will silently recover from common connection problems. If your service has multiple IP addresses, OkHttp will attempt alternate addresses if the first connect fails. This is necessary for IPv4+IPv6 and services hosted in redundant data centers. OkHttp supports modern TLS features (TLS 1.3, ALPN, certificate pinning). It can be configured to fall back for broad connectivity.

Certificate pinning sounds relevant to what we're doing here, considering our approach is to supply an alternate certificate. So what is it? According to the OkHttp docs:

Constrains which certificates are trusted. Pinning certificates defends against attacks on certificate authorities. It also prevents connections through man-in-the-middle certificate authorities either known or unknown to the application’s user. This class currently pins a certificate’s Subject Public Key Info as described on Adam Langley’s Weblog. Pins are either base64 SHA-256 hashes as in HTTP Public Key Pinning (HPKP) or SHA-1 base64 hashes as in Chromium’s static certificates.

Our monitoring setup is such a man-in-the-middle scenario: we use our own certificate authority (in this case, Burp Suite) to "re-secure" the actual connection from TransitApp, after we've monitored and tampered with the connection.

So, how do we get around certificate pinning? We'll need to get quite a bit more serious about our decompilation efforts, since we'll need to remove the hash of the existing certificate in the code and replace that with the hash of our own certificate. I roughly followed this guide for this step.

Link to this section APK Analysis

Android Studio helpfully includes an APK Analyzer tool which we can use to peek a bit deeper into the app. Create a new project,then drag and drop the TransitApp APK into the main window.

Unfortunately, method names have pretty much all been minified, so you'll see a bunch of u4, a5, o4, etc. Android Studio also doesn't let us view or modify the Java code within each method. However, note that even the OkHttp3 code seems to be minified, and I couldn't find any reference to CertificatePinner (although rg -a CertificatePinner returned a few matches, so maybe there's hope?)

An open-source tool called APKtool might save us. APKtool allows us to essentially decompile an APK into Smali (essentially an assembly listing for Java bytecode), make modifications, then recompile it. To start, let's see if we can find the certificate hash.

First, download the .jar from here, then run it with:

java -jar apktool_2.7.0.jar d Transit\ Bus\ \&\ Subway\ Times_5.13.5_Apkpure.apk

Finally, dive into the directory named after that APK. We're looking for the code that invokes CertificatePinner.

Link to this section Reading Smali Bytecode: Working Up

rg CertificatePinner

This seems to give quite a few results within the okhttp3 library: the implementation of certificate pinning, special handling in the connection class, and a few other uses. However, there is one result outside that library:

smali_classes2/com/masabi/justride/sdk/platform/AndroidPlatformModule2.smali91:.method private getCertificatePinner()Lokhttp3/CertificatePinner;107: new-instance v1, Lokhttp3/CertificatePinner$a;111: invoke-direct {v1}, Lokhttp3/CertificatePinner$a;-><init>()V206: invoke-virtual {v1, v3, v4}, Lokhttp3/CertificatePinner$a;->a(Ljava/lang/String;[Ljava/lang/String;)Lokhttp3/CertificatePinner$a;215: invoke-virtual {v1}, Lokhttp3/CertificatePinner$a;->b()Lokhttp3/CertificatePinner;250: invoke-direct {p0}, Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/platform/AndroidPlatformModule2;->getCertificatePinner()Lokhttp3/CertificatePinner;258: invoke-virtual {p1, v0}, Lokhttp3/OkHttpClient$a;->d(Lokhttp3/CertificatePinner;)Lokhttp3/OkHttpClient$a;

The result on line 111 looks perhaps the most interesting to us: invoking the constructor on the CertificatePinner class. However, it doesn't seem to be passing in any sort of hash. Let's consult the OkHttp documentation as to how CertificatePinners are constructed:

String hostname = "publicobject.com";CertificatePinner certificatePinner = new CertificatePinner.Builder().add(hostname, "sha256/AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA=").build();OkHttpClient client = OkHttpClient.Builder().certificatePinner(certificatePinner).build();Request request = new Request.Builder().url("https://" + hostname).build();client.newCall(request).execute();

Huh, okay, so we're really looking for a CertificatePinner.Builder. But rg CertificatePinner.Builder gives no results.

Here's where a Java quirk comes into play: Nested classes like CertificatePinner.Builder are represented internally using a dollar sign in place of the dot. So we're really looking for CertificatePinner$Builder. Make sure to escape it properly:

rg 'CertificatePinner\$Builder'

And... still no results. But don't lose hope yet--remember our experiments with APK Analyzer? Perhaps the name Builder got minified. Let's try to find any nested classes within CertificatePinner:

rg 'CertificatePinner\$'

It looks like there's a CertificatePinner$a, CertificatePinner$b, and CertificatePinner$c. The docs seem to show three nested classes: Builder, Companion, and Pin. Out of the three, it seems like Builder is the only one that should need to be used externally. Looking at the one result outside of the okhttp3 package:

smali_classes2/com/masabi/justride/sdk/platform/AndroidPlatformModule2.smali107: new-instance v1, Lokhttp3/CertificatePinner$a;111: invoke-direct {v1}, Lokhttp3/CertificatePinner$a;-><init>()V206: invoke-virtual {v1, v3, v4}, Lokhttp3/CertificatePinner$a;->a(Ljava/lang/String;[Ljava/lang/String;)Lokhttp3/CertificatePinner$a;215: invoke-virtual {v1}, Lokhttp3/CertificatePinner$a;->b()Lokhttp3/CertificatePinner;

We're looking for the call to Builder.add(), since that will pass in the pin as a hash. Again, the name .add() will be minified, so we'll need to be clever. Now that we've narrowed things down to a single file, we can start to read through and look for anything interesting. This method stands out (.line directives omitted for brevity):

.method private getCertificatePinner()Lokhttp3/CertificatePinner;.locals 8iget-object v0, p0, Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/platform/AndroidPlatformModule2;->sdkConfiguration:Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/internal/models/config/SdkConfiguration;invoke-virtual {v0}, Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/internal/models/config/SdkConfiguration;->getCertificatePins()Ljava/util/List;move-result-object v0new-instance v1, Lokhttp3/CertificatePinner$a;invoke-direct {v1}, Lokhttp3/CertificatePinner$a;-><init>()Vinvoke-interface {v0}, Ljava/util/List;->iterator()Ljava/util/Iterator;move-result-object v0:goto_0invoke-interface {v0}, Ljava/util/Iterator;->hasNext()Zmove-result v2if-eqz v2, :cond_0invoke-interface {v0}, Ljava/util/Iterator;->next()Ljava/lang/Object;move-result-object v2check-cast v2, Ljava/lang/String;iget-object v3, p0, Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/platform/AndroidPlatformModule2;->sdkConfiguration:Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/internal/models/config/SdkConfiguration;invoke-virtual {v3}, Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/internal/models/config/SdkConfiguration;->getHostname()Ljava/lang/String;move-result-object v3const/4 v4, 0x1new-array v4, v4, [Ljava/lang/String;const/4 v5, 0x0new-instance v6, Ljava/lang/StringBuilder;invoke-direct {v6}, Ljava/lang/StringBuilder;-><init>()Vconst-string v7, "sha256/"invoke-virtual {v6, v7}, Ljava/lang/StringBuilder;->append(Ljava/lang/String;)Ljava/lang/StringBuilder;invoke-virtual {v6, v2}, Ljava/lang/StringBuilder;->append(Ljava/lang/String;)Ljava/lang/StringBuilder;invoke-virtual {v6}, Ljava/lang/StringBuilder;->toString()Ljava/lang/String;move-result-object v2aput-object v2, v4, v5invoke-virtual {v1, v3, v4}, Lokhttp3/CertificatePinner$a;->a(Ljava/lang/String;[Ljava/lang/String;)Lokhttp3/CertificatePinner$a;goto :goto_0:cond_0invoke-virtual {v1}, Lokhttp3/CertificatePinner$a;->b()Lokhttp3/CertificatePinner;move-result-object v0return-object v0.end method

Let's step through what this is doing, using our intuition to bridge the gaps:

- Calling

SdkConfiguration.getCertificatePins(), which returns a list of some type (maybe Strings?) - Creating a

CertificatePinner.Builder(shown here as aCertificatePinner$a) - Iterating through the list of certificate pins

- For each pin, using a

StringBuilderto assemble a hash string (starting withsha256/) - Calling

.add()on theCertificatePinner.Builderobject with the constructed string for each pin - Returning the result of calling

.build()on theBuilder

This means we'll need to search a little bit deeper to find the hashes we seek, starting with getCertificatePins().

$ rg getCertificatePinssmali_classes2/com/masabi/justride/sdk/converters/config/SdkConfigurationConverter.smali454: invoke-virtual {p1}, Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/internal/models/config/SdkConfiguration;->getCertificatePins()Ljava/util/List;smali_classes2/com/masabi/justride/sdk/internal/models/config/SdkConfiguration.smali762:.method public getCertificatePins()Ljava/util/List;smali_classes2/com/masabi/justride/sdk/platform/AndroidPlatformModule2.smali99: invoke-virtual {v0}, Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/internal/models/config/SdkConfiguration;->getCertificatePins()Ljava/util/List;

The result with .method public is the definition of the getCertificatePins() method -- let's start there.

.method public getCertificatePins()Ljava/util/List;.locals 1.annotation system Ldalvik/annotation/Signature;value = {"()","Ljava/util/List<","Ljava/lang/String;",">;"}.end annotationiget-object v0, p0, Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/internal/models/config/SdkConfiguration;->certificatePins:Ljava/util/List;return-object v0.end method

Okay, so we're just returning the certificatePins field. It's just a classic "getter method." We can track down the field definition:

.field private final certificatePins:Ljava/util/List;.annotation system Ldalvik/annotation/Signature;value = {"Ljava/util/List<","Ljava/lang/String;",">;"}.end annotation.end field

Okay, so it's a private final List<String>. That's pretty standard. This essentially gives us two options: either these options are set in the constructor, or they're added later through another public method. Let's check the constructor first.

.method private constructor <init>(Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/util/List;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/util/List;Ljava/util/List;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;ZLjava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;Z)V.locals 2.annotation system Ldalvik/annotation/Signature;value = {"(","Ljava/lang/String;","Ljava/lang/String;","Ljava/lang/String;","Ljava/util/List<","Ljava/lang/String;",">;","Ljava/lang/String;","Ljava/lang/String;","Ljava/util/List<","Ljava/lang/String;",">;","Ljava/util/List<","Ljava/lang/String;",">;","Ljava/lang/String;","Ljava/lang/String;","Ljava/lang/String;","Ljava/lang/String;","Ljava/lang/String;","Z","Ljava/lang/String;","Ljava/lang/String;","Ljava/lang/String;","Z)V"}.end annotation

Oh god, that's 32 lines and we haven't even gotten to an implementation yet. Here's the part of the implementation that deals with the certificate pins:

move-object v1, p4iput-object v1, v0, Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/internal/models/config/SdkConfiguration;->certificatePins:Ljava/util/List;

So the pins are passed in as a list, in the fifth parameter (p4 is indexed starting at zero.) Let's keep following this wild goose chase: where is the constructor called?

$ rg 'SdkConfiguration;-><init>'smali_classes2/com/masabi/justride/sdk/internal/models/config/SdkConfiguration.smali211: invoke-direct/range {p0 .. p18}, Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/internal/models/config/SdkConfiguration;-><init>(Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/util/List;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/util/List;Ljava/util/List;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;ZLjava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;Z)Vsmali_classes2/com/masabi/justride/sdk/internal/models/config/SdkConfiguration$Builder.smali379: invoke-direct/range {v2 .. v21}, Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/internal/models/config/SdkConfiguration;-><init>(Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/util/List;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/util/List;Ljava/util/List;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;ZLjava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;ZLcom/masabi/justride/sdk/internal/models/config/SdkConfiguration$1;)V

Oh, duh, it's another builder. At least this one isn't minified? Let's take a look at the SdkConfiguration$Builder.smali file. Alongside brand, country code, and other parameters, we see a few points of interest.

Here's the definition of the certificatePins field on the builder. Note that it isn't marked final, meaning it probably gets assigned to somewhere.

.field private certificatePins:Ljava/util/List;.annotation system Ldalvik/annotation/Signature;value = {"Ljava/util/List<","Ljava/lang/String;",">;"}.end annotation.end field

Next in the file is the .build() method. It does some checks for null, but other than that, seems pretty boring. Scrolling down a bit, though, we see a definition for setCertificatePins():

.method public setCertificatePins(Ljava/util/List;)Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/internal/models/config/SdkConfiguration$Builder;.locals 0.annotation system Ldalvik/annotation/Signature;value = {"(","Ljava/util/List<","Ljava/lang/String;",">;)","Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/internal/models/config/SdkConfiguration$Builder;"}.end annotationiput-object p1, p0, Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/internal/models/config/SdkConfiguration$Builder;->certificatePins:Ljava/util/List;return-object p0.end method

There's no surprise here regarding what this method does (it just assigns the argument to the certificatePins field). However, now that we know the name of this method, we can try to look for it elsewhere.

$ rg setCertificatePinssmali_classes2/com/masabi/justride/sdk/converters/config/SdkConfigurationConverter.smali199: invoke-virtual {v2, v3}, Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/internal/models/config/SdkConfiguration$Builder;->setCertificatePins(Ljava/util/List;)Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/internal/models/config/SdkConfiguration$Builder;smali_classes2/com/masabi/justride/sdk/internal/models/config/SdkConfiguration$Builder.smali770:.method public setCertificatePins(Ljava/util/List;)Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/internal/models/config/SdkConfiguration$Builder;

It looks like the only place setCertificatePins is called is within SdkConfigurationConverter. This is an interesting class, and it's not immediately clear what it's doing. A few method names give us a clue, however:

convertJSONObjectToModel(JSONObject p1)convertModelToJSONObject(SdkConfiguration p1)

It would be really easy if the certificate pins were just stored in a JSON file somewhere... But find . -type f -name "*.json" comes up empty.

One quick sanity check: Is SdkConfigurationConverter even constructed? It could be that we're looking in the complete wrong part of the code here. Maybe our assumption about certificate pinning isn't correct after all?

Note that SdkConfigurationConverter has a private constructor and a public static create() method. Therefore, we should be searching for SdkConfigurationConverter.create().

$ rg 'SdkConfigurationConverter;->create'smali_classes2/com/masabi/justride/sdk/jobs/config/ProcessConfigurationDataJob.smali1096: invoke-static {}, Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/converters/config/SdkConfigurationConverter;->create()Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/converters/config/SdkConfigurationConverter;

Okay, so it's used somewhere at least. Is ProcessConfigurationDataJob invoked anywhere? It looks like it has a create() method, just like SdkConfigurationConverter.

$ rg 'ProcessConfigurationDataJob;->create'smali_classes2/com/masabi/justride/sdk/AndroidJustRideSdkBuilder.smali121: invoke-static {v0}, Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/jobs/config/ProcessConfigurationDataJob;->create(Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/platform/crypto/PlatformSignatureVerifier;)Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/jobs/config/ProcessConfigurationDataJob;

And just to finish going up the chain, where is this instantiated?

$ rg AndroidJustRideSdkBuilder[...]smali_classes2/com/thetransitapp/droid/shared/TransitApp.smali524: invoke-static {}, Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/AndroidJustRideSdk;->builder()Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/AndroidJustRideSdkBuilder;532: invoke-virtual {p1, p0}, Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/AndroidJustRideSdkBuilder;->application(Landroid/app/Application;)Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/AndroidJustRideSdkBuilder;540: invoke-virtual {p1, v0}, Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/AndroidJustRideSdkBuilder;->configuration(Ljava/io/InputStream;)Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/AndroidJustRideSdkBuilder;548: invoke-virtual {p1}, Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/AndroidJustRideSdkBuilder;->build()Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/AndroidJustRideSdk;[...]

Here we are: TransitApp.smali, which seems like the entrypoint to the application. It seems like it passes some sort of InputStream to the builder--maybe this is the JSON data we're looking for?

Here's the method that invokes this (it's just labeled j, since we're back into minified code):

.method private synthetic j(Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/Throwable;)V.locals 2if-eqz p2, :cond_0return-void:cond_0const/4 p2, 0x0:try_start_0new-instance v0, Ljava/io/ByteArrayInputStream;invoke-virtual {p1}, Ljava/lang/String;->getBytes()[Bmove-result-object p1const/4 v1, 0x0invoke-static {p1, v1}, Landroid/util/Base64;->decode([BI)[Bmove-result-object p1invoke-direct {v0, p1}, Ljava/io/ByteArrayInputStream;-><init>([B)V:try_end_0.catch Ljava/lang/Exception; {:try_start_0 .. :try_end_0} :catch_1.catchall {:try_start_0 .. :try_end_0} :catchall_1:try_start_1invoke-static {}, Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/AndroidJustRideSdk;->builder()Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/AndroidJustRideSdkBuilder;move-result-object p1invoke-virtual {p1, p0}, Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/AndroidJustRideSdkBuilder;->application(Landroid/app/Application;)Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/AndroidJustRideSdkBuilder;move-result-object p1invoke-virtual {p1, v0}, Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/AndroidJustRideSdkBuilder;->configuration(Ljava/io/InputStream;)Lcom/masabi/justride/sdk/AndroidJustRideSdkBuilder;[...]

Okay, so v0 is our InputStream. We call getBytes() on the string parameter, then Base64 decode it, then pass that into the ByteArrayInputStream constructor. So where is the string passed into j? Searching just that file (assuming it's the entry point) for ->j gives another method, b:

.method public static synthetic b(Lcom/thetransitapp/droid/shared/TransitApp;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/Throwable;)V.locals 0invoke-direct {p0, p1, p2}, Lcom/thetransitapp/droid/shared/TransitApp;->j(Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/Throwable;)Vreturn-void.end method

It looks like this is a bridge method, used to support generics.

Now, is this method called anywhere? Doing a regex search in invoke-static \{.*\}, Lcom/thetransitapp/droid/shared/TransitApp doesn't find anything related to it.

Link to this section Reading Smali Bytecode: Working Down

Maybe we missed something somewhere. Doing a bit of research, it looks like the entrypoint to an Android application is in a class that inherits from Application and overrides the onCreate method. Does our TransitApp class fit the bill? Let's check. Right at the top of the file, we see:

.class public Lcom/thetransitapp/droid/shared/TransitApp;.super Landroid/app/Application;.source "TransitApp.java"# interfaces.implements Lac/b;

Okay, so that .super line confirms it. Let's look at the onCreate() method. It's quite long, so let's break it down.

.method public onCreate()V.locals 4invoke-super {p0}, Landroid/app/Application;->onCreate()V

We start by calling the base Application's implementation of onCreate() -- pretty standard stuff for inheritance. We also have four local variables.

invoke-static {p0}, Landroidx/emoji2/text/c;->a(Landroid/content/Context;)Landroidx/emoji2/text/j;move-result-object v0const/4 v1, 0x1if-eqz v0, :cond_0invoke-virtual {v0, v1}, Landroidx/emoji2/text/e$c;->c(I)Landroidx/emoji2/text/e$c;move-result-object v0invoke-virtual {v0, v1}, Landroidx/emoji2/text/e$c;->d(Z)Landroidx/emoji2/text/e$c;move-result-object v0new-instance v2, Lcom/thetransitapp/droid/shared/TransitApp$a;invoke-direct {v2, p0}, Lcom/thetransitapp/droid/shared/TransitApp$a;-><init>(Lcom/thetransitapp/droid/shared/TransitApp;)Vinvoke-virtual {v0, v2}, Landroidx/emoji2/text/e$c;->b(Landroidx/emoji2/text/e$e;)Landroidx/emoji2/text/e$c;move-result-object v0invoke-static {v0}, Landroidx/emoji2/text/e;->g(Landroidx/emoji2/text/e$c;)Landroidx/emoji2/text/e;:cond_0

AndroidX, also known as Jetpack, is a set of Android libraries provided by Google to handle common tasks. androidx.emoji2 is a library to support modern emoji on older platforms, including text rendering and emoji pickers. The method calls here are minified, but we can safely rule this out as uninteresting for now. That said, the if statement that seems to construct a new instance of TransitApp definitely strikes me as odd.

invoke-virtual {p0}, Landroid/content/Context;->getCacheDir()Ljava/io/File;move-result-object v0invoke-static {v0}, Lcom/thetransitapp/droid/shared/data/NetworkHandler;->setCacheDir(Ljava/io/File;)V

This seems to be setting the directory to store cached assets.

invoke-static {p0}, Lmb/a;->a(Landroid/content/Context;)Landroid/content/SharedPreferences;move-result-object v0iput-object v0, p0, Lcom/thetransitapp/droid/shared/TransitApp;->a:Landroid/content/SharedPreferences;

This code uses the SharedPreferences class in some form, likely to retrieve some form of user preferences and store a handle to them for later.

invoke-static {p0}, Lcom/thetransitapp/droid/shared/util/j2;->c(Landroid/content/Context;)Imove-result v0invoke-virtual {p0}, Landroid/content/Context;->getTheme()Landroid/content/res/Resources$Theme;move-result-object v2invoke-virtual {v2, v0, v1}, Landroid/content/res/Resources$Theme;->applyStyle(IZ)V

This handles differentiating between dark and light theme.

invoke-direct {p0}, Lcom/thetransitapp/droid/shared/TransitApp;->d()Vinvoke-static {p0}, Lcom/thetransitapp/droid/shared/util/z2;->i(Landroid/content/Context;)Vinvoke-static {}, Lcom/thetransitapp/droid/shared/util/z2;->g()Ljava/lang/String;move-result-object v0invoke-static {}, Lcom/google/firebase/crashlytics/FirebaseCrashlytics;->getInstance()Lcom/google/firebase/crashlytics/FirebaseCrashlytics;move-result-object v2invoke-virtual {v2, v1}, Lcom/google/firebase/crashlytics/FirebaseCrashlytics;->setCrashlyticsCollectionEnabled(Z)Vinvoke-virtual {v2, v0}, Lcom/google/firebase/crashlytics/FirebaseCrashlytics;->setUserId(Ljava/lang/String;)V

This code grabs some sort of user ID, stores it in v0, then uses it to set up the Firebase Crashlytics crash reporter.

const-string v1, "com.thetransitapp"filled-new-array {v1}, [Ljava/lang/String;move-result-object v1invoke-static {v1}, Lz2/b;->a([Ljava/lang/String;)Vnew-instance v1, La3/k;invoke-direct {v1}, La3/k;-><init>()Vinvoke-virtual {v1}, La3/k;->b()La3/k;move-result-object v1invoke-virtual {v1}, La3/k;->d()La3/k;move-result-object v1invoke-virtual {v1}, La3/k;->c()La3/k;move-result-object v1invoke-static {}, La3/a;->a()La3/d;move-result-object v2invoke-virtual {v2, v1}, La3/d;->f0(La3/k;)La3/d;move-result-object v1const-string v2, "3687b056476e15e4fe1b346e559a4169"invoke-virtual {v1, p0, v2, v0}, La3/d;->A(Landroid/content/Context;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;)La3/d;move-result-object v1invoke-virtual {v1}, La3/d;->q()La3/d;move-result-object v1invoke-virtual {v1, p0}, La3/d;->r(Landroid/app/Application;)La3/d;move-result-object v1const-wide/32 v2, 0xea60invoke-virtual {v1, v2, v3}, La3/d;->c0(J)La3/d;

Checking the a3/a.smali file, we get this header:

.class public La3/a;.super Ljava/lang/Object;.source "Amplitude.java"

Amplitude looks like some kind of analytics application, which makes sense for something that would be set up in an onCreate() call.

const/4 v1, 0x0invoke-static {v1}, Lcom/revenuecat/purchases/Purchases;->setDebugLogsEnabled(Z)Vnew-instance v1, Lcom/revenuecat/purchases/PurchasesConfiguration$Builder;const-string v2, "JfhIYqEpBxRrLkgLLizTDhRqyoPguWdY"invoke-direct {v1, p0, v2}, Lcom/revenuecat/purchases/PurchasesConfiguration$Builder;-><init>(Landroid/content/Context;Ljava/lang/String;)Vinvoke-virtual {v1, v0}, Lcom/revenuecat/purchases/PurchasesConfiguration$Builder;->appUserID(Ljava/lang/String;)Lcom/revenuecat/purchases/PurchasesConfiguration$Builder;move-result-object v0invoke-virtual {v0}, Lcom/revenuecat/purchases/PurchasesConfiguration$Builder;->build()Lcom/revenuecat/purchases/PurchasesConfiguration;move-result-object v0invoke-static {v0}, Lcom/revenuecat/purchases/Purchases;->configure(Lcom/revenuecat/purchases/PurchasesConfiguration;)Lcom/revenuecat/purchases/Purchases;

This code sets up the RevenueCat integration for in-app subscriptions.

The method continues on, but nothing else in it looks all that notable -- just some error handling stuff. But looking into each of these integrations is making me realize: what exactly were we looking at before?

Link to this section So, what exactly is JustRide?

Remember, we first found our JustRide method in com/masabi/justride/sdk/platform/AndroidPlatformModule2.smali. Are we sure that this is related to what we're trying to find?

Looking up JustRide, it advertizes itself as a mobile ticketing platform. They provide an SDK for integrating ticket purchases into other apps. It seems like TransitApp just includes the JustRide SDK for this functionality, so its use of certificate pinning is largely irrelevant.

Okay, back to the drawing board.

Link to this section Network Security Config

Doing a bit more research, I stumbled upon a GitHub project called AddSecurityExceptionAndroid that claims to be able to enable reverse engineering. It links to a few Android reference pages.

First, it mentions Network Security Configuration, which allows application developers to implement certificate pinning using a configuration file instead of any code changes. Maybe this is what we're after? It gives an example AndroidManifest.xml file for this:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?><manifest ... ><application android:networkSecurityConfig="@xml/network_security_config"... >...</application></manifest>

Let's check this against TransitApp's AndroidManifest.xml to see if it uses this. I've grabbed only the <application> tag, since the file is quite large:

<application android:allowBackup="true" android:appComponentFactory="androidx.core.app.CoreComponentFactory" android:extractNativeLibs="false" android:fullBackupContent="@xml/backup_descriptor" android:icon="@mipmap/ic_launcher" android:label="@string/app_name" android:largeHeap="true" android:localeConfig="@xml/locales_config" android:logo="@drawable/action_bar_icon" android:name="com.thetransitapp.droid.shared.TransitApp" android:roundIcon="@mipmap/ic_launcher_round" android:theme="@style/SplashScreen" android:usesCleartextTraffic="true">

I don't see a networkSecurityConfig option, and furthermore, the app specifically opts into "cleartext traffic" (HTTP). Let's keep looking.

The other linked source is a blog post from 2016. Emphasis mine:

In Android Nougat, we’ve changed how Android handles trusted certificate authorities (CAs) to provide safer defaults for secure app traffic. Most apps and users should not be affected by these changes or need to take any action. The changes include:

- Safe and easy APIs to trust custom CAs.

- Apps that target API Level 24 and above no longer trust user or admin-added CAs for secure connections, by default.

- All devices running Android Nougat offer the same standardized set of system CAs—no device-specific customizations.

For more details on these changes and what to do if you’re affected by them, read on.

This is the exact approach we were trying: adding our own CA to try to pull off a man-in-the-middle attack on ourselves.

Reading further in the blog post, it seems like apps need to use a Network Security Config setting to opt into user-added CAs. Since TransitApp does not supply a Network Security Config, this is probably what's blocking us from using our own CA here.

Link to this section AddSecurityExceptionAndroid

The AddSecurityExceptionAndroid script works by overwriting the network_security_config.xml file and adding the relevant attribute to the application tag in AndroidManifest.xml. Let's run it on our .apk and see if it works.

First, set up a debug keystore in Android Studio, following the documentation. I chose the following settings based on what I found in the addSecurityExceptions.sh file:

| Setting | Value |

|---|---|

| Key store path | /Users/breq/.android/keystore.jks |

| Password | android |

| Alias | androiddebugkey |

| Password | android |

| Validity | 25 (default) |

After creating the key, you can exit out of Android Studio.

git clone https://github.com/levyitay/AddSecurityExceptionAndroidcd AddSecurityExceptionAndroidcp ~/Downloads/Transit\ Bus\ \&\ Subway\ Times_5.13.5_Apkpure.apk ./transit.apk./addSecurityExceptions.sh -d transit.apk

We use -d to make the .apk debuggable -- I don't know if this will be useful or not, but there's no reason not to.

When running this, I ran into this issue:

W: /tmp/transit/AndroidManifest.xml:82: error: attribute android:localeConfig not found.W: error: failed processing manifest.

Based on this GitHub issue, it seems like I need to make modifications to the APK before attempting to recompile it. I modified the addSecurityException.sh script to wait before recompiling:

@@ -122,6 +122,9 @@ if [ $makeDebuggable ] && ! grep -q "debuggable" "$tmpDir/AndroidManifest.xml";mv "$tmpDir/AndroidManifest.xml.new" "$tmpDir/AndroidManifest.xml"fi+echo "Make any changes now in $tmpDir"+echo "Press ENTER when done..."+readjava -jar "$DIR/apktool.jar" --use-aapt2 empty-framework-dir --force "$tmpDir"echo "Building temp APK $tempFileName"

Then, in another terminal, I opened the temporary directory (/tmp/transit in my case). I didn't see a locales_config.xml, but I did notice that the AndroidManifest.xml included the parameter android:localeConfig="@xml/locales_config". I removed the localeConfig parameter from AndroidManifest.xml, then continued the addSecurityException.sh script, which worked this time.

Link to this section Dynamic Analysis: Take 2

We'll need to uninstall the old app from our emulator before installing the APK. Boot up the emulated device and uninstall TransitApp, then drag and drop the new APK onto the emulator.

Doing this, I get an error: INSTALL_FAILED_NO_MATCHING_ABI: Failed to extract native libraries. Actually, when I try to use the unmodified .apk I downloaded, I get the same error. Looking into /tmp/transit/lib, we only see x86_64 -- the sketchy website lied about what architecture the APK is.

We can try another sketchy site. Looking in /tmp/transit/lib now, we see arm64-v8a -- perfect. We can verify that this APK installs correctly. (Make sure you have internet access in your emulator -- I forgot to launch dnsmasq and had some issues with this.)

We can go through the same steps of running the script and removing the android:localeConfig parameter. Install this APK, and boom: our modified TransitApp build is running in our emulator. Some parts of the app don't seem to be working: maybe this is because our proxy isn't running?

Start the proxy, verify the settings in /etc/hosts, and restart dnsmasq for good measure.

Holy shit. We're finally getting something.

Link to this section Here's Where The Fun Begins

We can already see some requests just from opening the app and signing in. Here's the response for /v3/users/me right now:

HTTP/2 200 OKX-Powered-By: ExpressContent-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8Content-Length: 298Etag: W/"12a-pknx7teDN3n3f6xhsnm1RmASA/M"Vary: Accept-EncodingDate: Fri, 16 Jun 2023 22:29:36 GMTVia: 1.1 googleAlt-Svc: h3=":443"; ma=2592000,h3-29=":443"; ma=2592000{"subscriptions":[],"royale":{"user_id":"9702c35a82984e76","avatar":{"username":"Floppy Sensei","username_type":"generated","image_id":"💾","color":"e3131b","foreground_color":"ffffff","visibility":"public"}},"main_agencies":["MBTA"],"time_zone_name":"America/New_York","time_zone_delta":"-0400"}

Here's where we can confirm our hypothesis about the emoji shuffle being done client-side. Looking at the network logs while clicking "shuffle," nothing seems to be happening in the network console. Perfect!

We'll edit our username and icon by accepting one of the suggestions. Here's the generated request (I've changed the User ID and removed the authorization token):

PATCH /v3/users/b1dfb2047e8bd5eb HTTP/2Host: api.transitapp.comAccept-Language: en-USAuthorization: Basic [REDACTED]Transit-Hours-Representation: 12User-Agent: Transit/20900 transitLib/114 Android/13 Device/sdk_gphone64_arm64 Version/5.14.6Content-Type: application/jsonContent-Length: 196Connection: Keep-AliveAccept-Encoding: gzip, deflate{"avatar":{"color":"f3a4ba","foreground_color":"804660","image_id":"🍦","image_type":"emoji","subscribed":false,"username":"Cone Extravaganza","username_type":"generated","visibility":"public"}}

And here's the response:

HTTP/2 200 OKX-Powered-By: ExpressContent-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8Content-Length: 180Etag: W/"b4-0vP9yEjHVjjz1iTkW1gCoYEcQG4"Vary: Accept-EncodingDate: Fri, 16 Jun 2023 22:32:01 GMTVia: 1.1 googleAlt-Svc: h3=":443"; ma=2592000,h3-29=":443"; ma=2592000{"id":"b1dfb2047e8bd5eb","avatar":{"color":"f3a4ba","foreground_color":"804660","username":"Cone Extravaganza","username_type":"generated","image_id":"🍦","visibility":"public"}}

Let's modify the request a bit. Turn on Burp's Intercept tool, then randomize the name and icon again:

PATCH /v3/users/b1dfb2047e8bd5eb HTTP/2Host: api.transitapp.comAccept-Language: en-USAuthorization: Basic [REDACTED]Transit-Hours-Representation: 12User-Agent: Transit/20900 transitLib/114 Android/13 Device/sdk_gphone64_arm64 Version/5.14.6Content-Type: application/jsonContent-Length: 191Connection: Keep-AliveAccept-Encoding: gzip, deflate{"avatar":{"color":"ffce00","foreground_color":"855323","image_id":"😐","image_type":"emoji","subscribed":false,"username":"Feral Voovie","username_type":"generated","visibility":"public"}}

Let's quickly swap out the payload for this:

PATCH /v3/users/b1dfb2047e8bd5eb HTTP/2Host: api.transitapp.comAccept-Language: en-USAuthorization: Basic [REDACTED]Transit-Hours-Representation: 12User-Agent: Transit/20900 transitLib/114 Android/13 Device/sdk_gphone64_arm64 Version/5.14.6Content-Type: application/jsonContent-Length: 191Connection: Keep-AliveAccept-Encoding: gzip, deflate{"avatar":{"color":"ff42a1","foreground_color":"000000","image_id":"🎈","image_type":"emoji","subscribed":false,"username":"Brooke Chalmers","username_type":"generated","visibility":"public"}}

Things didn't update in the UI. However, if we sign out and sign back in... There we go!

Thanks for joining me on this little adventure! I worked on this blog post every now and then over the course of a few months. Getting this to work in the end was such a great feeling -- if my initial hypothesis had been wrong, I still would've learned a lot, but the payoff would've been quite a bit less fun. And if you see a 🎈 emoji rider around Boston, feel free to say hi!